Monday, January 18, 2021

Why Do We Love Complementary Colors?

Monday, December 21, 2020

More Explorations in Extended Parallel Threadings

|

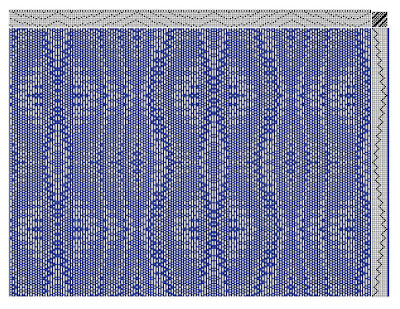

First, how to create the design itself? I think I found the original pattern, a twill pattern with elements of a Crackle threading, on Handweaving.net. Can't remember, exactly, because it could also have been on Pinterest. Both are great places to scan weaving drafts for ideas. Here's what the original draft looks like.

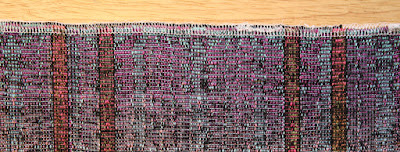

As for Rep (below): Well, not so great, but I think it was partly owing to my choice of wefts, where I alternated 20/2 cotton (thin weft) and black rayon chenille (thick weft). I think this sample would have been better if I changed my sett, making it much denser, and chose something thicker and less textured than the chenille for the thicker weft. Nevertheless, I see some potential here!

Tuesday, November 17, 2020

Gebrochene, Echo and Jin with Fiberworks: Putting 'The Earl' Through His Paces

Hard to see in the above image, but if you look closely you can find blue and aqua in the boxes above the threading, indicating the colors of the warp threads below.

Next, create a 4/4 ascending twill tieup, which is a classic Echo tieup. The elementary way to do this is to draw it in by clicking on the boxes you want -- but to do it faster, you can just fill in the tieup for the first treadle and then click on the "Tieup" dropdown menu, select "Twill Repeat" and then "Step Up," "Step by 1," "Treadles per group 1" and "Apply."

The motifs are still a bit squashed, right? There are ways to fix that -- one of them being to change the treadling.

Monday, October 19, 2020

Finally... a Design I Like!

Tuesday, September 8, 2020

Designing Echo as Double Weave for 16 Shafts

An aside: With double weave, the shafts that are "raised" to weave the bottom layer are actually being lowered from the perspective of the bottom layer, because the bottom layer is weaving upside down (from the weaver's perspective). It's helpful to think of the tieup for the bottom layer as a sort of photo negative, where up is down (black is white) and down is up (white is black).

Note that the second half of the tieup for both layers is totally blank. That's where Stubenitsky's ratio comes in. For this, I tried a tieup with a ratio of 4:4, meaning that, in the second half of the treadling above the ground tieup, 4 shafts are raised and 4 shafts are down in an ascending order for both layers (top and bottom layers, on odd and even-numbered treadles).

Here's how that 4:4 ratio looks.

Next I created a tieup with a 5 to 3 ratio, which looks like this.

Name Drafts Aren't Just for Overshot....

Above is a name draft using -- why not? -- the name Michelangelo, employing an Echo threading and a twill tieup and treading. A name draft...

-

I think it's Elvis Costello who said, "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture." You could say the same ...

-

Last Saturday at the Weaving and Fiber Arts Center, I taught a class on "Getting the Blues: Natural Dyeing with Indigo and Woad."...

-

In 1921, Johannes Itten -- a painter and teacher at Germany's famed Bauhaus School -- published The Color Star , a small book featurin...