This is a case where you

can judge a book by its cover: One, it's written by Ann Richards, a weaver who for decades has achieved a singular beauty in her work. And two, the photo itself captures you, presenting a detailed image of her elegantly constructed "origami" cloth.

The text and photos do not disappoint. Richards, who trained as a biologist before studying weaving at the West Surrey College of Art and Design (now the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham), brings her skills of scientific analysis and her love of nature to bear on her art. In Chapter 1, "Endless Forms Most Beautiful," next to sketches of a dragonfly wing detail and a cross section of its edge, she shares a photo of one of her pleated fabrics. (All photos and images are provided courtesy of Ann Richards.)

Sketch, detail of a dragonfly wing

Cross-section, the front part of the wing

Detail of a pleated fabric woven by Richards, with the caption:

"Warp: Linen. Weft: Crepe silk and hard silk,

with picks of linen at intervals

serving as 'struts' to stiffen the pleating."

If you were to look at a cross-section of the woven fabric, you would delight in seeing that the pleats are quite similar to those of the dragonfly wing.

"Weaving Structure and Substance" is not a how-to book, although it does offer instructions for designing, materials, and finishing. Foremost, it's a discussion and analysis of how Richards and other weavers she admires create their work. The book has four parts: "Nature as Designer," "Resources for Design," "Designing for Fabric Qualities," and "Designing Through Making." There are chapters devoted to fibers and yarns, structures, the quest for textural qualities and forms, sampling, and the notion of "reflective practice." Further, there is an extensive bibliography as well as a list of online resources and suppliers.

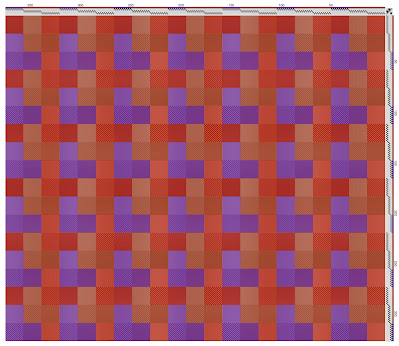

The photos are inspirational. Below is a piece she calls "Soft Pleat Scarf," showing both the front and the back. She offers these details: "This silk and linen scarf has a striped effect created by the reversal of the pleats. The weft colour remains the same throughout so this is a 'structural' stripe that disappears when the fabric is stretched to its full width. Warp; Linen 77 lea, 72 epi and spun silk 60/2 Nm, 54 epi. Weft: Spun silk 210/2Nm, 48 ppi."

The delicacy, refinement, and simplicity of this piece represents the highest level of planning, design, and resolution. And yet the concept is easy to grasp: The shifting blocks -- seen in the thin horizontal white and black stripes -- are achieved by reversing the structure from the back to the front, requiring two blocks in the threading.

It is her depth of understanding and ability to exploit the unique potential of her materials that produce such inimitable designs. Appropriately, she quotes Darwin: "Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved."

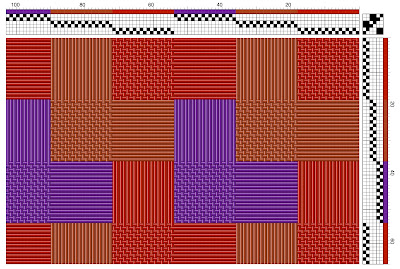

Richards's signature pieces are necklaces, collars, and bracelets with origami folds.

Her caption: "These triple spiral bracelets are assembled

from offset sections of pleated fabric. Warp: Silk/steel 82/2 Nm (pleats)

and spun silk 60/2 Nm cords). Weft: Crepe silk and polyester reflective yarn."

This is Richards's second book from Crowood Press, her first being the best-selling Weaving Textiles that Shape Themselves. As with the first, her new book includes lavish photos of her work and that of Wendy Morris, Stacey Harvey-Brown, the late Junichi Arai (founder of Nuno), and many others (including me, I'm proud to say).

Note: I think by now you can guess I'm a huge fan -- to the point that about six years ago I traveled to London to study with her at the Handweavers Studio and Gallery. Her cordiality and relaxed demeanor belied the energy, observation, and creativity she brings to her work.

Dimensional, tactile weaving is a sub-category of weaving that spans broadly, from fulled fabrics to Leno gauze to exploiting the properties of specialized yarns such as crepe, overtwist, and elastic, to name a few. I highly recommend this book to weavers who are interested in what can broadly be termed "dimensional weaving" -- and also to those who are keen to learn more about how attention to materials and structure can improve their work.

WEAVING STRUCTURE AND SUBSTANCE by Ann Richards. The Crowood Press, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR, United Kingdom. Hardcover. 175 pages. $32.45.

Oh yes, and if you happen to be in London between now and February 2, 2022, be sure to stop by the Handweavers Studio and Gallery at 140 Seven Sisters Road. There, you'll be able to see first-hand what these techniques can achieve.